It’s the second Sunday in Lent. It’s raining in Krakow, but I feel like I’m in the desert — out in the wilderness of this fasting time, with a lot of barren sand ahead of me before I get to the Promised Land.

It’s already been a long Lent. I want some relief.

And relief in the desert put me in mind of a story from the Bible.

A class I follow with Rabbi Mike Feuer from Yeshivat Sulam Yaakov in Jerusalem helped me to understand the story. The following reflections are based on his teaching:

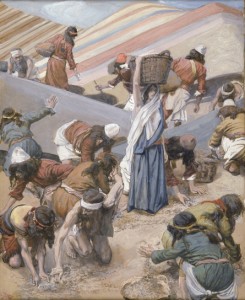

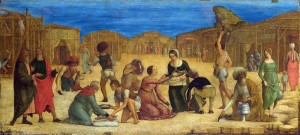

In chapter sixteen of the book of Exodus, we are fresh out of Egypt. The People of Israel are just beginning their sojourn in the wilderness. They have a long way to go, and they’re anxious.

But God says: Don’t worry, I have a gift for you. It’s going to come to you throughout your time in the desert. It is manna.

Manna in the desert. Perhaps we could use some of that now.

The Bible says the word manna comes from “man,” which is a question-word and begins the phrase, “What is it?” or, more literally, “Whose is it?” — “Man hu? (מָן הוּא)”

We get some not-so-clear descriptions in Exodus of what this food-thing is. Is it like a dew? A frost? Flakes or seeds that you gather up and make into a pie? Does it taste like honey-cake; does it taste like anything you want it to be? Perhaps it tastes like mother’s milk.

The manna comes in amounts that are exactly as much as you need; you can’t try to hoard it or it will rot. It doesn’t appear on the Sabbath: it comes in a double delivery on Friday morning.

The manna is a gift — a gift on God’s own terms.

God says: I want you to take some of this manna and put it in a jar and show it to later generations, that they may know that this is how I fed the people in the desert (Ex 16:32). The manna is a sign for the people of Moses’s time, and it is a sign for us who come after.

Contemporary Jews consider it a mitzvah – a blessed activity – simply to read this story of the manna. In reading, they hope to digest its lessons of total dependence on the Lord, and remember God’s unfailing, unfaltering love. The People of Israel are a stiff-necked people; an obstreperous bunch. So are all of us. Yet the story of the manna is an answer to the griping and the complaining of the People of God – in the desert or anywhere else; then or since.

Complaining: we do not criticize a baby for complaining. The baby is happy if it gets what it needs. But if you don’t respond to the baby right away, it squawks.

And the People of Israel began to squawk. “Is God in our midst or not?” they asked.

But what kind of question is that? These are people who are actually following a pillar of fire. They just went through the Red Sea. They remembered the ten plagues. And still they ask, “Is God with us?” What kind of question is that?

It’s the question of a baby.

A baby lacks a mental skill called object permanence. In developmental psychology, object permanence is the understanding that things continue to exist even when they cannot be observed. Babies don’t know that.

A lack of object permanence is why the game of “Peek-A-Boo” is fun. The baby smiles and laughs when I cover my face and then reveal it — and it will laugh again and again no matter how many times I do the same thing. It’s such a stupid game, but the baby thinks “Peek-A-Boo” is the most delightful pastime ever invented.

And that is the stage the People of Israel are in here.

The very minute, the very second that God is out of sight, they start to worry. Are we not safe? Are we not loved? Where is God? As soon as God is not holding our hand, as soon as He is not obviously present among us, we say He is gone.

We think God has abandoned us. Just like the Israelites in the desert.

Well, it’s Lent. And we’re all in the wilderness. We’re on the road, together, to the Promised Land.

We are well out of Egypt. Can’t go back. And there’s not going to be another parting of the Red Sea – a dramatic or cinematic moment that forces us to acknowledge the presence of God. That was an important moment; a birth for a whole People. But now there is only our daily allotment of manna.

In the long run, we are going to have to grow up – no longer be spiritual babies – and accept, and know, that God is nigh.

The manna is a lesson; a form of training in the skill of knowing and accepting that we are in the hands of God. Eat your manna and stop whining.

Manna – man hu? – Whose is it? It’s God’s. And only His.

And so are we.

“Eat your manna and stop whining” – I love it☺. I’ve been needing to hear this. Thank you! God bless you.

Thanks, Liliana. We preach what God gives us. And if that’s ALL we preach, we’re doing good.

In the Talmud, tractate Yoma dealing with the Day of Atonement, there is an extensive non-legal excursus about manna. Two pearls from that discussion: One, what blessing did the Israelites pronounce before eating the manna? (A Jew may not enjoy any physical benefit from the world without pronouncing a blessing.) The normal blessing for bread is (translated) Blessed are You, Lord our G-d, King of the Universe, Who brings forth bread from the earth. The Israelites in the desert, before eating the manna, blessed “… Who brings forth bread from heaven”. Wow! The second insight I wish to share is that there were three categories of Israelites in the desert, defined by what they did with their manna when they ate it. The righteous ate it as it was given. The wicked cooked it. Those somewhere in between ground it up before eating it. This is a metaphor for how we accept blessings from G-d. Do we receive them as given, with unmitigated gratefulness, or are we ungrateful and feel we have to put our own stamp on it to say we did something? Or do we try to be holy and nervously mess with it in opposition to our good intentions? Erik, come and see me when you are in Israel.