As regular readers know, I emigrated to Poland from Milwaukee, a port city on Lake Michigan.

No one knows where Milwaukee is when I’m in Poland, so I usually say, “If you head north from Chicago along the lakeshore, the next big city you encounter is Milwaukee.”

People nod as if they understand — at least the conversation can go on.

That northern route is the path I take each time I come back from Poland to visit my family in America. My parents usually pick me up at O’Hare, the Chicago airport. Then we go up on one of the Interstate Highways built across the continent in the 1950s. (They were supposed, among other things, to help the U.S. Army in case of Soviet invasion.)

As the car noses over the frontier between Illinois and Wisconsin, I start looking for a copper dome over the horizon. A bend in the road, and there it is: the massive brown balloon supported by sandstone piers with clocks facing the cardinal directions. It’s a symbol of my city. But it’s not a library or some great civic temple. There’s a cross atop that dome. It’s the Basilica of Saint Josaphat. Poles built it.

…

To get to Saint Josaphat, you head west from the highway for a few blocks past the duplexes with tarpaper shingles, past the Serbian restaurant and Nail Sensations, right alongside Kościuszko Park (that’s Ka-zji-as-ko Park).

Stop the car somewhere on the street, maybe in front of the funeral parlor. Lock your doors: this isn’t a nice neighborhood.

Cross the street and get yourself up the steps and through the door, pushing on the handle marked with the seal of the Customs Service (I’ll explain later).

Let the door close behind you. Exhale. Heaven.

The Basilica of Saint Josaphat: an angel holds the holy water font. The walls vibrate with sconces and scrollwork and trompe l’oeil marble. A slick stone floor stretches to the main altar, 50 yards away. Beyond the baldachin, in vivid oils, a bishop in red is ready to die.

That man, of course, is Josaphat Kuntsevych (Jozafat Kuncewicz), of the Order of Saint Basil the Great, a monk and “archeparch” killed at Vitebsk in November of 1623. Here he is treated as an icon of the Catholic West against Eastern Darkness. The altarpiece was executed by Gonippo Raggi, a painter sent to Milwaukee from Rome by Pope Pius XI, who as papal nuncio in Warsaw had survived the invasion of Poland by the Bolsheviks. Pius loved Polonia.

By the way, it’s not a politically-correct picture: an Orthodox cleric in a high black kamilavka points his bony finger in accusation at Josaphat while a peasant with a big red beard raises the axe to murder him. Ecumenical dialogue, anyone?

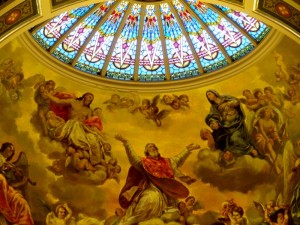

Look up: the dome that soars 76 meters above the street is blank on the outside, but here on the inside it swarms with life. Apostles. Fathers of the Church. Celestial bodies. Eight windows with eight different Madonnas. Giant canvasses that follow Raphael. And, in huge gold letters around the base, this verse from the First Book of Kings: “I have hallowed this house, which thou hast built, to put my name there for ever; and mine eyes and mine heart shall be there perpetually.” Except it’s in Polish, lest we forget who made this place. “Bom obrał i poświęcił to miejsce, aby tam imię moje było na wieki, a żeby tam trwały oczy moje i serce moje po wszystkie dni.” It’s straight from Wujek’s Bible and it’s all laid out in bright leaf, right down to the last Ę and Ł — to the consternation of anglophone Americans.

Here prayed the Poles who clung to a South Side as unglamorous then as it is now. Poles who, some of them, could barely read in their own language much less in English. Poles who emigrated “za chlebem” — as Sienkiewicz put it — and ended up in Chicago or Pittsburgh or Buffalo or Milwaukee bending over a blast furnace or tanner’s vat while their wives put their knees on the floorboards and their fingers in some lady’s washbucket.

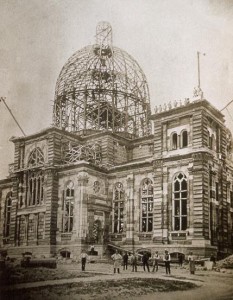

These same Poles built a basilica. They built it. Because they could not afford to hire labor, they gave their own work. The washerwoman came home, made the children something to eat, then shifted debris from the foundations of the edifice, one apron-load at a time. Her husband drove the horse that hauled the sledge that carried the dirt to the dump site west of the Kinnickinnic River. Her brother hustled blocks up the scaffold. People still tell these stories in Milwaukee.

The new immigrants had no building materials, either. But they did have a wily pastor named Grutza. He sensed an opportunity when a new government office-building in Chicago was brought down for structural flaws. He snapped up the cast-off stone and fittings for pennies and shipped it all to Milwaukee on flatcars. An architect from Württemberg (by way of Ohio) was engaged to magic the stones into place. The Postal Service’s brass railings were hoisted to the choir and the Customs Service’s shield stayed on the doorknobs. Soon the archbishop was gliding in to celebrate High Mass, right past the patriotic mural of the Battle of Racławice. It was 1901.

Five weeks after the dedication, Father Wilhelm Grutza, who had overseen the building process from start to finish, expired. Let’s hope he ended up with Josaphat.

Go there on a Sunday now. The basilica parish is administered by Conventual Franciscans, some with names like Poczworowski (Paz-ła-rał-ski, of course). They have one of the best choirs in town. (I have heard this choir give a hesitant rendition of Serdeczna Matko, which they call “our parish song.”) The grand organ throbs and thickens the air into honey.

Ladies in fur coats who’ve come in from the suburbs — some, the granddaughters of washerwomen — sit next to Mexican maids, the new arrivals, who rustle in nylon jackets.

And after the Sanctus they’re all on their knees. Because this place is holy, hallowed by God, and from time to time, in this time as in all times, God’s people need to stop in and see Him.

What a wonderful story this is!

Przepiękna, poruszająca historia. Poznałam ją tylko dzięki temu, że poprosiłam rodzinną poliglotkę o pomoc. Może ktoś zechciałby przetłumaczyć i zamieścić polskie tłumaczenie? Naprawdę szkoda, że tylko angielskojęzyczni czytelnicy bloga mogli dotąd przeczytać o tym, jak polscy emigranci żyli w Ameryce i co było dla nich najważniejsze. Dziękuję, Ojcze, piękne jest to, co Ojciec napisał!

Dziękuję Pani. Jakoż że na razie nie ma tłumaczenia na język polski polecam filmik “Virtual Tour” bazyliki. https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/4/41/BasilicaSJ_EDIT.webmsd.webm

wow! thank you!

Bardzo często moje refleksje odbiegają od głównego tematu. Tak jest również teraz. Nigdy nie byłem w Milwaukee i poza tym wpisem Milwaukee kojarzą mi się z jednym: piwem Old Milwaukee. Wszystkie amerykańskie piwa są dla mnie wyjątkowo niestrawne. Piwo Old Milwaukee poza wyjątkowo odrażającym smakiem ma atrybut unikalny nawet wśród piw amerykańskich. Jest nim duszący odór. Uważam, że producent powinien informować konsumentów o ryzyku zatrucia związanego ze spożywaniem tego napoju w pomieszczeniach zamkniętych. Całe szczęście, że wraz z imigrantami do USA przyjechały piwa z Polski :).