Today is the feast of many martyrs: Saint Andrew Kim Tae-gŏn (김대건 안드레아), the first native-born Korean priest, and of Paul Chong Hasang (정하상 바오로), a lay apostle, and their companions.

Look at the farmer who cultivates his rice fields, wrote Saint Andrew. In season he plows, then fertilizes the earth; never counting the cost; he labors under the sun to nurture the seed he has planted. When harvest time comes and the rice crop is abundant, forgetting his labor and sweat, he rejoices with an exultant heart.

Andrew wrote this just before he died. It was 1846. He was 25 years old.

Christ is the farmer, the sower of seed (Matthew 13). Saint Andrew, Saint Paul, and their friends sowed, too. And if Jesus sowed wheat in Judea, why shouldn’t Koreans sow rice?

In Korea as everywhere, what Tertullian wrote is true: semen est sanguis christianorum — literally, the blood of Christians is seed. (Apologeticus, 50, s. 13)

So the local church, which today includes over 5 million faithful, 10 percent of the South Korean population, is grateful to those who went before — and were slain.

In state-led persecutions in 1839, 1866 and 1867, 103 Korean Christians were tortured and murdered in odium fidei, in hatred of the faith. Today’s saints are the cream of the crop.

Korea’s church dates back to the 17th century. It was founded by Asian lay missionaries, not European clergymen. Their closest link to the Church hierarchy was in China. When priests came hundreds of years later, they discovered a functioning Catholic community already in place — albeit an odd, priestless one.

Even in the 19th century, the layman Paul Chong Hasang had to go outside his country to find a prelate. He crossed the border with China nine times and took a scathing route through mountains and desert to solicit the aid of the bishop of Beijing. He pleaded with the Portuguese Cayetano Pires Pireira, C.M. — known in Chinese as 畢學源 (Bi Xueyuan) — to send priests to his homeland. He wrote to Pope Gregory XVI through this bishop requesting the establishment of a diocese in Korea.

The priests came in 1837: Bishop Laurent-Marie-Joseph Imbert, who had been consecrated earlier that year for just this purpose, sneaked across from Manchuria to Korea with two other Frenchmen. According to some accounts, it was the arrival of these foreigners that provoked a new persecution — but records show some sort of crackdown was already going on.

Laurent-Marie-Joseph Imbert, M.E.P., was martyred, too, in 1839. He was declared a saint by John Paul II in 1984. His relics lie in Singapore.

The new bishop took a shine to Paul Chong Hasang and taught him Latin and theology. He was about to ordain him… when the ax man came round.

Paul was captured. He gave the judge a written statement defending Catholicism. After reading it, the judge said, “You are right in what you have written; but the king forbids this religion, it is your duty to renounce it.” A neat argument.

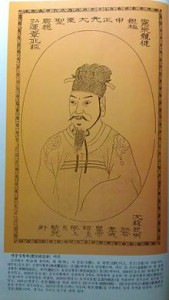

The king at the time was this man, Heonjong of the centuries-old Joseon dynasty. Kings don’t like new things.

Hasang replied, “I have told you that I am a Christian, and will be one until my death.” It wouldn’t be long in coming. They say he was calm during torture; that at the end he was bound to a cross on a cart. He is supposed to have been — even — cheerful. It was a martyrdom: explicit, pure and simple.

The need for there to be real martyrs in order for a church to grow is one if those things we affirm without thinking. At a time here in Europe when even high-ranking churchmen bewail a withering Church, we may no longer have the luxury of thoughtlessness.

An icon of the Korean martyrs, mixing Eastern Orthodox with East Asian with Latin Catholic imagery. Marked in English. Why not? (pinterest)

Of course, martyrdom in the narrow sense — being murdered for Christ — is not something we seek. Yet we are all martyrs — μάρτυρες, witnesses. And if the sword or the cross or the hammer and sickle come, so be it.

We’re ready.

We hope.

Not Lenin in his bathrobe and hat, but a statue of Saint Andrew at Jeoldusan Martyrs’ Shrine, Tojeong-ro, Seoul (bike.go.kr)

The gift of the martyr — and I mean the kind who spills blood — is the model of generosity. Nothing of the self is held in reserve. Life itself is poured out for Christ and for the Church, often in spectacular ways (on a grill, upside down, in a circus) but more often — in recent decades — in bestial anonymity. You can’t be a martyr and stint.

Shrine of Saint Andrew in Lolomboy, Bocaue, Bulacan, the Philippines. Andrew spent time here as a seminarian. On the grounds, the pagoda of China meets a version of Spanish Baroque. (pinoyetchetera.blogspot.com)

In the Office of Readings for today, we read the final exhortation of Andrew Kim Taegon, priest and martyr. When you think of the conditions in which he died, it’s amazing that we have these words at all.

He says to us, The Lord is like a farmer and we are the field of rice that he fertilizes with his grace and by the mystery of the incarnation and the redemption irrigates with his blood, in order that we will grow and reach maturity.

Saints Andrew and Paul and their companions were not just the rice in the field, they were the sowers, too, following the Lord. And they mixed their blood with the blood of Christ to water the land. They didn’t just sprinkle it, as one waters flowers from a dainty can. They swamped the land, submerging it entirely as rice farmers do. No stinting.

Christ does the same: is that not the image of God’s mercy — abundant, overflowing, never stingy? Gushing out, rushing out, until all is given and all at last are saved?

How awful — how awesome — to know we need to give that much.

Comments - No Responses to “Blood and rice”

Sorry but comments are closed at this time.