Long ago, God said through His prophet, “I will remove the heart of stone from your bodies and give you a heart of flesh” (Ezekiel 36:26).

Today Jesus shows us how to let a heart of flesh defeat a heart of stone. He shows us how to roll back the stone and unseal the tomb; how to stone the sin but save the sinner. He does it all through mercy.

The Gospel for this Sunday, the Fifth Sunday of Lent, is one I love. I’m sure a lot of people do. But we’ve heard it so often, it’s hard to hear afresh.

Perhaps it’s time to look again at the basics. Let’s talk about sin, ladies and gentlemen:

We know that sin, by which we — like our parents — choose to divorce ourselves from the One who is Life, is the most deadly thing there is. Notice that not a stone was cast in today’s Gospel. No one was killed. But some were in a state of spiritual death. And that includes not only the woman, who may have harbored many sins, but also – probably – a lot of men in the crowd.

No physical death today, but spiritual death is everywhere.

The only one in the whole picture who is free of sin is Jesus. And the only difference between the sinners around Him lies in how they react to Him.

It’s easy to identify sin in others. We like to do it. And that seems to have been the specialty of the Pharisees as John presents them. They saw sin all over — just not in themselves. And when it came time for them to stand in the light of the truth, they fled.

That is why, one by one, they back away from Jesus when he says, “Let him who is without sin cast the first stone.”

But of course this is Jesus’s question to each one of us. “Which of you is without sin?” And when we make the Pharisees into biblical bogeymen – when we caricature them and make them monstrous and strange – we are escaping this question as pusillanimously as they did.

Which of us is without sin?

An honest answer to that question is the beginning of conversion. It is the beginning of life in God. And no matter how religious and well-intentioned we are (surely some Pharisees were religious and well-intentioned), we cannot bring others to God or preach the Word or even love another person until we have that life in us.

Restoring that life requires bravery. It demands honesty and trust in God. And an adulteress is about to show us how to do it.

Perhaps the worst thing is not the sin itself – as many an old confessor will tell you — it’s getting used to sin, living with sin until it becomes a false friend. You think you’re holding steady for a while, you and your sin, but a niggling shame pushes you step by step away from the Lord who asks, “Which of you is without sin?”

It’s a question we’d rather avoid.

Saint Augustine wrote about this. But perhaps the best description in English of the corrosive effects of the comfortable long-term sin is from Brideshead Revisited (Evelyn Waugh, 1945). There’s a years-long episode of adultery near the back of the book. Then, on a long and queasy sea voyage, the numbed and habituated adulteress finally — finally! — comes to hate her sin:

Living in sin, with sin, by sin, for sin, every hour, every day, year in, year out. Waking up with sin in the morning, seeing the curtains drawn on sin, bathing it, dressing it, clipping diamonds to it, feeding it, showing it round, giving it a good time, putting it to sleep at night with a tablet of Dial if it’s fretful. Always the same, like an idiot child carefully nursed, guarded from the world. ‘Poor Julia,’ they say, ‘she can’t go out. She’s got to take care of her little sin. A pity it ever lived,’ they say, ‘but it’s so strong. Children like that always are. Julia’s so good to her little, mad sin.’

That passage has the power to make us feel queasy, too. It’s devastating.

And yet a moment like this is life-giving. It’s the moment we stop escaping – the point where we embrace the truth of our condition in front of God, ourselves, and everybody — and begin to let Jesus do His work.

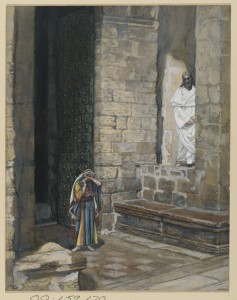

And that’s what happened today. All of this woman’s accusers creep away, and only she and Jesus are left standing there. Only the sinner and the Sinless One. It’s a lot like what happens in the confessional.

The woman knew she had sinned. She knew that, in a sense, Jesus had the right to stone her. After all, when He said, “Let he who is without sin cast the first stone,” He was referring, in a way, to Himself. And, scared though she was, this woman doesn’t try to manage Jesus or cajole Him or channel His reaction. She abandons herself entirely to His will.

And then she hears the most beautiful words in the world: “Has no one condemned you? Neither do I condemn you. Go, and sin no more.”

Without Jesus, the adulteress would have been buried in her grave that afternoon. But now she is at peace. She stands up, dries her eyes, and walks on.

These are the facts: We all need mercy. Sin has no remedy but the mercy of God. And no one but Jesus has the power to say, “I forgive you your sins.”

Our basilica here in Krakow is filled with confessionals. We have a whole chapel dedicated to them, but they spill over and line the side aisles of the nave, too. Then they spill out into the cloister walk. Lots of wooden boxes. They’re there for a reason.

Jesus awaits me. How long will I make him wait?

I know I have sinned. It’s only a question of what I’m going to do about it. Will I back away, whispering to myself the lie that all is fine with me (thanks very much)?

Or will I – might I, like this nameless woman, stand in the light, abandon myself to the judgment of the Lord, and come away with a clean heart and a new life?

There is no life, no love – no freedom – without a clean conscience.

Blessed are the pure in heart, says the Lord.

And ain’t that the truth.

Comments - No Responses to “Stone away”

Sorry but comments are closed at this time.