Today is the Feast of the Nativity of the Blessed Virgin Mary. In its holy liturgy, the Church gives us the very first lines of the Gospel of Matthew. Remember this?

“Abraham became the father of Isaac,

Isaac the father of Jacob,

Jacob the father of Judah and his brothers.

Judah became the father of Perez and Zerah,

whose mother was Tamar.

Perez became the father of Hezron,

Hezron the father of Ram,

Ram the father of Amminadab….”

This is what Matthew called “The book of the genealogy of Jesus Christ.” It’s the famous “Family Tree” Gospel. Problem is, by the time we get to Ram and Amminadab, the congregation is usually meditating on lunch and a nap.

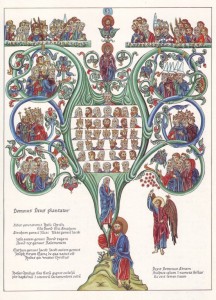

A Stammbaum Christi or “Family Tree of Christ” illustration based on the Hortus deliciarum of Herrad of Landsberg (12th c.)

One workday at — yes — lunchtime, I walked out of Mass abruptly — something I had never done before and haven’t done since. Everything seemed normal at first. We all sang the Alleluia as usual, but when the priest got to the pulpit, he refused to read this Gospel. We were all left standing there, rocking on our toes, ready to hear the Word, while this priest explained (in his own words) how unnecessary it was to read “all those strange names.” Poor man. I figured: I came here to get the Gospel, and if he’s not giving it, I’ll go.

He should have done a little digging. In order to “get” this Gospel, you have to know how to read it. Then, it gets exciting.

First there is the symbolism of numbers. In tracing Jesus from Abraham, Matthew uses a scheme of 3-times-14 generations (Mt 1:17). In ancient Hebrew numerology, two is the number of the divinity. The number 14 is two times 7, and 7 is the number of perfection. These symbolic calculations are meant to show the presence of God in every generation.

In Jesus, of course, God is not just present but incarnate. Matthew is telling us that Jesus came at a divinely-ordained time. And with the advent of the Savior, the whole of the history of salvation — Abraham, Isaac, Jacob, Moses, David, sin and exile and return… all that jazz — comes to fruition.

But there’s more. Remember: this is Mary’s feast. In this Gospel there is a hidden feminine code. Cherchez la femme, as they say.

Look at the whole text. In this long list of names, there is a major innovation. The classic genealogies consisted of a long list of forefathers — men. But Matthew slips in five women: Tamar, Rahab, Ruth, Bathsheba (“the wife of Uriah”)… and Mary.

And what a brash bunch of women they are.

None of these women, before Mary, were native Hebrews. All of them were in some way irregular or engaged in questionable behavior. All of them showed a lot of chutzpah. And without them — every one of them — Jesus would not have been born.

Who was Tamar? Look at Genesis 38:1-30. This lady was a Canaanite, a widow, and she dressed herself up as a a prostitute as a way of getting Judah (her father-in-law, who had prevented her from remarrying) to lie with her and give her a son. Her plan worked: Genesis 38:15-16 reports, “When Judah saw her, he thought she was a prostitute, for she had covered her face. Not realizing that she was his daughter-in-law, he went over to her by the roadside and said, ‘Come now, let me sleep with you.’” (Tamar is considered righteous because, even if by deception, she fulfilled the prescription of the Law and took what she was owed — motherhood in a levirate union. Literally, “levir” means “brother-in-law”.) Two sons, Perez and Zerah, were the result. And Perez was one of the great-granddads of Jesus.

Rahab didn’t just dress like a prostitute, she was one. (She was a “sacred” temple prostitute, not a streetwalker.) And she wasn’t Jewish either. But she used her position in Jericho to help the Chosen People conquer the Promised Land. She, too, was a sneak: Signaling to the enemy, “she tied the scarlet cord in the window.” (For the whole exciting story, see Joshua 2:1-21). The plan worked. And Rahab, with Salmon, conceived Boaz — another ancestor of the Lord.

Boaz’s wife was foreign, too — a Moabite named Ruth. She was another widow, and she did something similar to what Tamar had done, spending the night with Boaz in order to oblige him to stay with her and give her a son. The Book of Ruth (3:7-8) paints a comical picture: “When Boaz had finished eating and drinking and was in good spirits, he went over to lie down at the far end of the grain pile. Ruth approached quietly, uncovered his feet and lay down. In the middle of the night something startled the man, and he turned and discovered a woman lying at his feet.” (For more, see Ruth 3:1-15; 4:13-17. The pulp paperbacks at the supermarket don’t have anything on this.)

And who was Bathsheba? An innocent Hittite woman lusted after by King David. The King sent her husband to death in battle and then summoned and impregnated her. (See 2 Samuel 11:1-27). Bathsheba was abused. But she survived and gave birth to a great king, Solomon, David’s heir — another ancestor of Jesus.

These are not the women you would have picked to be in the world’s most illustrious family album.

The fact they’re included shows that God was for real when He decided to take flesh and assume the human condition in all its messiness. If you were trying to convince people that a pretender was the Messiah, you would sanitize his background. The fact that these are Jesus’s grannies — and we proudly announce them as such — adds credibility to the Faith.

Thanks to these women — all of them foreign, in irregular situations, and full of guts — God brought his Son into the world.

But what is Mary doing in this rowdy crowd? She was virtuous in every way. She was a daughter of Israel, not a foreigner. But she was, in her own way, full of guts.

The guts are expressed in one word: Fiat. “Be it done unto me according to your word.” In saying yes to that angel, Mary was taking one heck of a leap.

And then, before being married to Joseph, Mary became pregnant. That certainly seemed irregular.

Thank God, Joseph was, as the Gospel says, “a righteous man” (Mt 1:19). He wasn’t righteous by the rigorists’ lights. Some Pharisees would have had him turn Mary over to be stoned. That was the prescribed punishment, after all. (It’s hard not to look away from the specter of a stoned Virgin and Jesus crushed in her womb.)

But Joseph was righteous in the eyes of God, not men. He quietly spared Mary, then listened to the voice of his Maker coming to him in a dream, and married her. Thanks to Joseph’s justice, Jesus was born. And so, although it was not he who sired Jesus, the entire genealogy in Matthew’s Gospel boils down… to Joseph!

Here is the key difference between Mary and the four mothers who came before her: Mary is the first daughter of the New Covenant. And the justice of Joseph her spouse is the righteousness of the New Law.

Our God is an awesome God. On this feast of Mary, look at this boring list of names and marvel. Stare open-mouthed and wonder at the work of the Lord.

God said to Moses: “I will do signs such as were never seen upon the earth, nor in any nation: that this people, in the midst of whom thou art, may see the terrible work of the Lord which I will do.” (Exodus 34:10)

Mary said: “My soul proclaims the greatness of the Lord, my spirit rejoices in God my Savior, for He has looked with favor on his lowly servant. From this day all generations will call me blessed. The Almighty has done great things for me and holy is His name. He has mercy on those who fear Him in every generation.” (Luke 1:46-50)

Comments - No Responses to “Bad girls of the Bible”

Sorry but comments are closed at this time.